The Ossarium Death Expert of the Month Series

Every month we will present one "Death Expert" with 3 short questions and a picture describing his/her relation to death.

September 2018

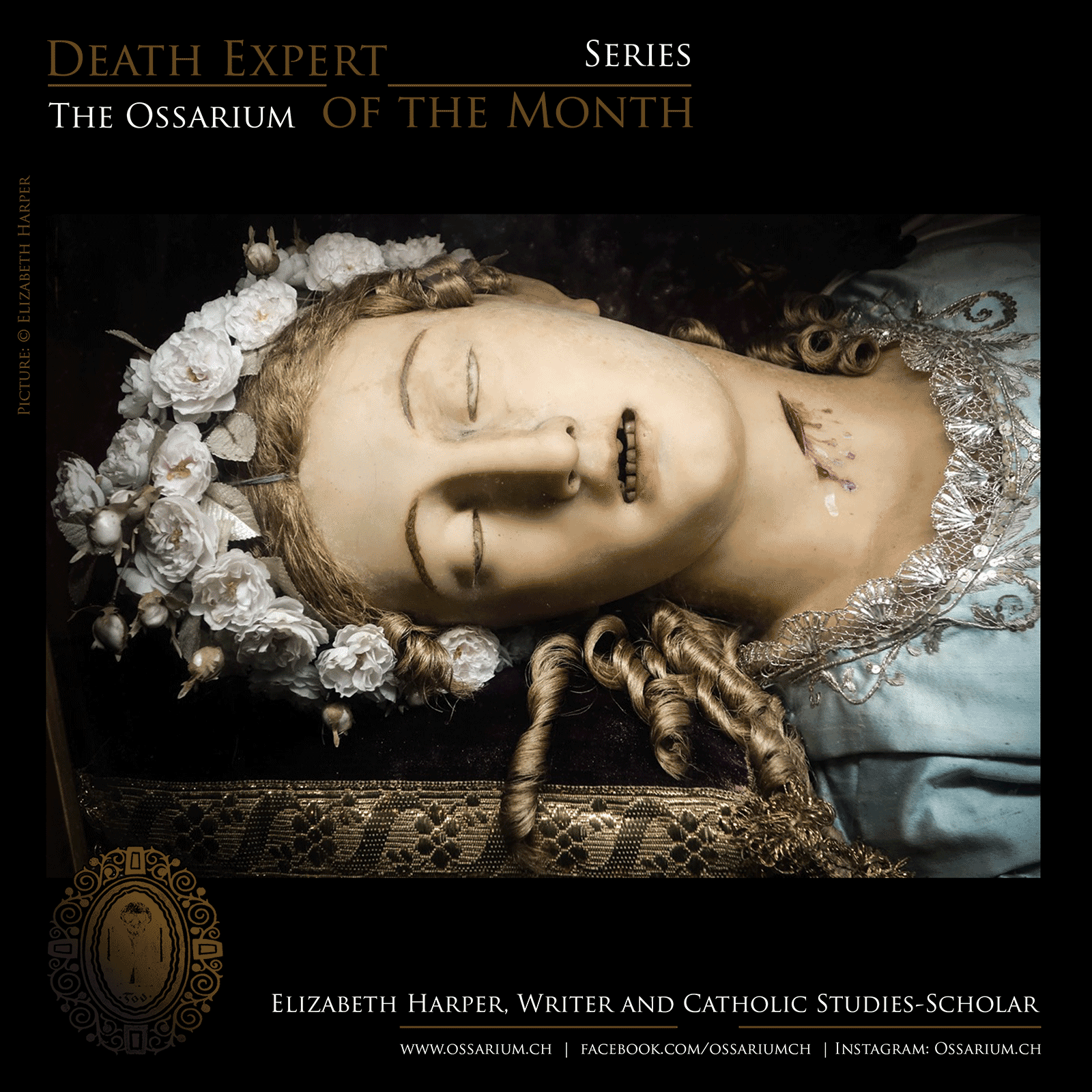

Elizabeth Harper

Writer and Catholic Studies-Scholar, Los Angeles

1 What does the picture show? How is it related to your occupation?

This is a photo I took of the wax body of St. Vittoria. Her bones are embedded inside the representation of her. She’s a saint from the Roman catacombs and she’s on display in Santa Maria della Vittoria in Rome, right across the church aisle from Bernini’s Ecstasy of St. Teresa. Plenty of tour groups come in to see the Bernini, but I’ve never seen a guide address St. Vittoria’s body, even though a lot of people are curious. And if you look her up online, there’s a lot of misinformation. For example, several articles call her incorrupt (a complex phenomenon when the body of a saint doesn’t decay for a period of time) but that’s not correct. I started writing about these under-explained corners of the Catholic Church because their histories are fascinating.

2 What does death represent for you personally?

I grew up in an Italian Catholic family so I’ve always had the kind of spooky comfort with death that comes from growing up in a church where it’s pretty normal to see dead bodies (of the saints anyway in the form of relics). So initially, my goal was to write for the general public and contextualize some of the more macabre things they might find in Catholic churches. I focused on Europe and particularly Italy since churches there can be major tourist attractions and the relics inside tend to be poorly explained to tourists, if they’re explained at all. So initially my relationship to death was generally positive. In a very Catholic way, I considered my relationship to dead saints on-going through my research and visits. I thought of them as kind of friends-at-large who I might bump in to at any time via a venerated finger or a skull.

As I researched more, I became increasingly interested in female mystic saints and how their bodies became enshrined in the patriarchal context of the Church. Death immediately factored into the lives of many of these saints because their bodies (by virtue of being female) were considered sin incarnate. So they would torture themselves through a practice called mortification and often utilized starvation and self-inflicted pain as a way to purify themselves. Some came to the brink of death; others died. While the Church is very clear that suicide is a mortal sin, these holy women were caught in an agonizing contradiction. By equating their bodies that kept them alive with sin, the only truly good women were dead ones. And this worked, in its own horrible way, for a certain subset of women who died from these practices and went on to become saints. But then their bodies, the ones they hated and punished, went on to be venerated by the overwhelmingly male institution that taught them to hate their bodies in the first place.

This immediately resonated with me as a woman and a (more or less) recovered anorexic. The trap that I found myself in, where food and flesh was sinful and denial and self-harm was virtuous, was one that had much older and deeper roots than I had previously considered. Learning about these saints (and the poor women who were never rewarded with sainthood but imitated those that were) was a big step in learning to embrace life (and sustenance) and reject the cultural trap that had been set for me.

Today, I still embrace thinking about death and even befriending the dead. (It’s why I keep photographing and writing about saints.) It’s a way of learning about the past, empathizing across hundreds of years and affirming that life is short and what you do with your time matters. However I’m careful to reject the idea of death being a more pure or virtuous state of being for a woman than life. I try not to fetishize the dead, editing out what’s messy and inconvenient about them, because by doing that I’m not honouring the idea that the dead are fully human, that the boundary between the living and the dead should be flimsy, and one day I (and everyone else I know) will pass right through it.

3 Can you tell us about an event related to death that you will never forget.

I went to Bonito, a tiny town in Southern Italy, to write about an allegedly miracle-working mummy who everyone just calls “Uncle Vincent”. He initially sat in the parish church but the Vatican took issue with a non-saint (in fact an anonymous corpse who was named Vincent posthumously) being displayed, in the nude no less, and venerated in a church. So instead of burying him, a group of people from Bonito who had emigrated to America sent money back to build him his own little shrine where he still sits today. They solved the naked problem by amputating his penis which seems drastic to me, but I don’t make the rules. On the day I went to see him, I really got the Southern-Italian run-around when I asked to unlock his shrine but eventually Uncle Vincent and I got to meet and I published a piece about him in Lapham’s Quarterly. He has a bit of a reputation as a miracle worker and vengeful ghoul so I keep a prayer card with his picture on it in my wallet, just so he doesn’t think I forgot about him.

June 2018

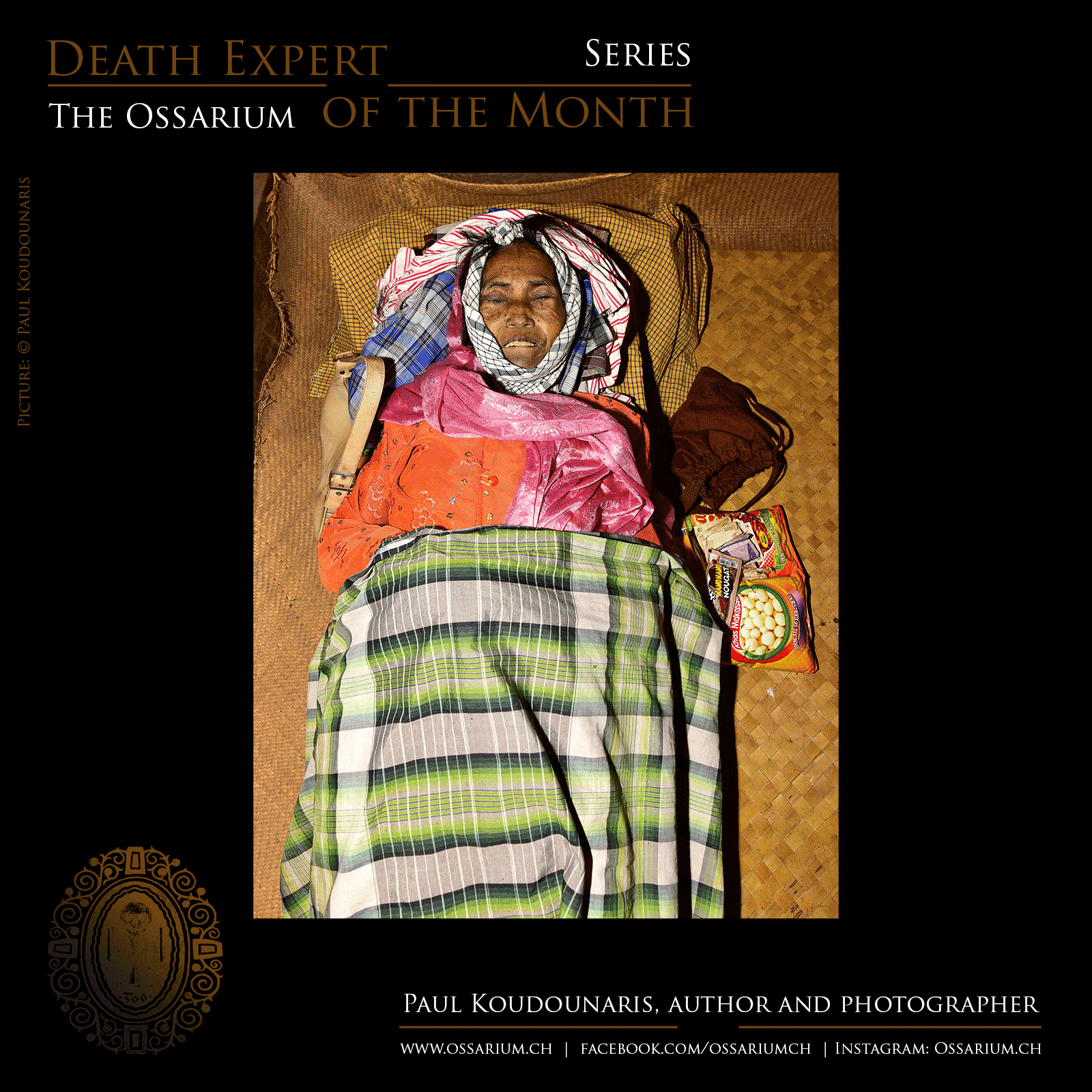

Dr. Paul Koudounaris

Author and photographer, Los Angeles

1 What does the picture show? How is it related to your occupation?

This photo shows a dead grandmother in a hut in Tana Toraja. Of course, it's part of my work in that I travel the world and photograph various death-related customs and rituals involving the human body, but mostly we're using this photo because it directly references what I will be discussing in my answers to the second and third questions--after I answered them I went back to the first question and decided I might as well use this specific photo.

2 What does death represent for you personally?

I've spent a lot of time trying to figure out the answer to this question. It's not easy. There's a certain death culture nowadays that's trendy online which I think skirts it, "death" becoming anything from a tombstone to a Victorian memento mori to a brain in a jar of formaldehyde. But death isn't any of those things. Those are trappings which surround it. And coming up with a functional definition for what death is and how it functions in society is incredibly hard. Try it. Really try it. It's hard. It's not a physical object so you have to clear away all the material culture that surrounds--and which I think actually serves distract us from it, since part of what death must be involves the negation of material culture.

Just from the preceding it should be obvious that I could go on quite awhile on this topic, but to cut to the end, what I finally came up with is this: "death" is a border. It's the border between two potential social groups, the living and the dead. But death is not being "dead" and we should not mistake the two. Nor is death the same thing as "dying," and again we should not mistake them. It's not merely a semantic point. Being dead is a biological condition in which various bodily functions have ceased (heart, brain activity), and it's pretty universal: someone who is dead over there in Zurich is dead here in Los Angeles too. Dying is the process of those functions ceasing. But death is the border between the dead and the living, and thus it has implications beyond biology.

Because that border governs the interaction between the living and the dead, it can structured differently depending on the area or time period. In some instances death is a soft border through which the living and the dead are encouraged to interact. We find this in many ancient cultures and even still today in many non-Western cultures, where the living are encouraged to continue a dialogue with the dead. In some cases the interaction is even physical (for example, the Ma'nene in Tana Toraja or the Fiesta de las Ñatitas in Bolivia, these are very soft borders). In other cases, as generally in contemporary American or European societies, the border is quite firm and association beyond it is considered perverse or taboo.

This means that "death" is actually relative. To some people this sounds wrong at first, or counter-intuitive. But that's because the concept of death is so hard for us to think about that we have it confused with being dead and dying. Because actually I think it's pretty sensible. Being dead is universal, but death is the border between the living and the dead, and therefore each society will consider it differently, according to its own traditions. So in Tana Toraja, with death being a very soft border, at the Ma'nene people will not only speak to their dead relatives, they will bring them from the tombs, dress them, and walk around holding them. And doing this there is totally acceptable and correct. And . . . if someone tried that in Zurich, well they would be arrested and written up in the newspapers as a deranged person, because it is totally unacceptable and incorrect there. Both sides have it right--within their society. It's a matter of how "death" as a boundary is structured in each place.

3 Can you tell us about an event related to death that you will never forget?

Yes, sure. Since I have been using the Ma'nene in the previous answer, why not stick with that? When I was in Toraja a couple years ago for the festival I was staying in a village in the mountains near a group of tombs--villages there basically being a small collection of huts all belonging to one family unit. So I had hung around for the better part of the week, traveling the valley as different villages would open their tombs, and photographing people taking out their dead relatives and dressing them, etc. The last day I was there, just before I was to depart, a woman from my little village came to me and said, "So I've noticed you're really interested in all this stuff with the dead people. I completely forgot to mention this, but did you know our grandmother is dead and living in the hut next to yours? Would you like to meet her?" (Yes, the woman in the photo from question 1).

First of all, consider the wording. "Dead and living." It wasn't a mistake on her part per se. The grandmother is dead yes, and by living she meant residing, but to her that language wouldn't really be a contradiction because death isn't fatalistic there the way it is here--it's simply a transition. Anyway, beyond that, can you imagine in Zurich or here in Los Angeles?--"Ah, did I forget to mention that my dead grandmother is in the room next to you? I guess it totally slipped my mind." A dead woman next door would be a very big deal! In Toraja, it really isn't. Because she is dead, but she's not really gone. Because death, as a I defined it, as a border, is very different there, and an interaction is encouraged beyond it. And yes--I went and met grandmother. She looked great, and we sat down with and spoke to her. The way we would in my society with an elderly lady who was perhaps bed-ridden. Anyway, it all goes back to the idea of how a society chooses to structure death as a border.

May 2018

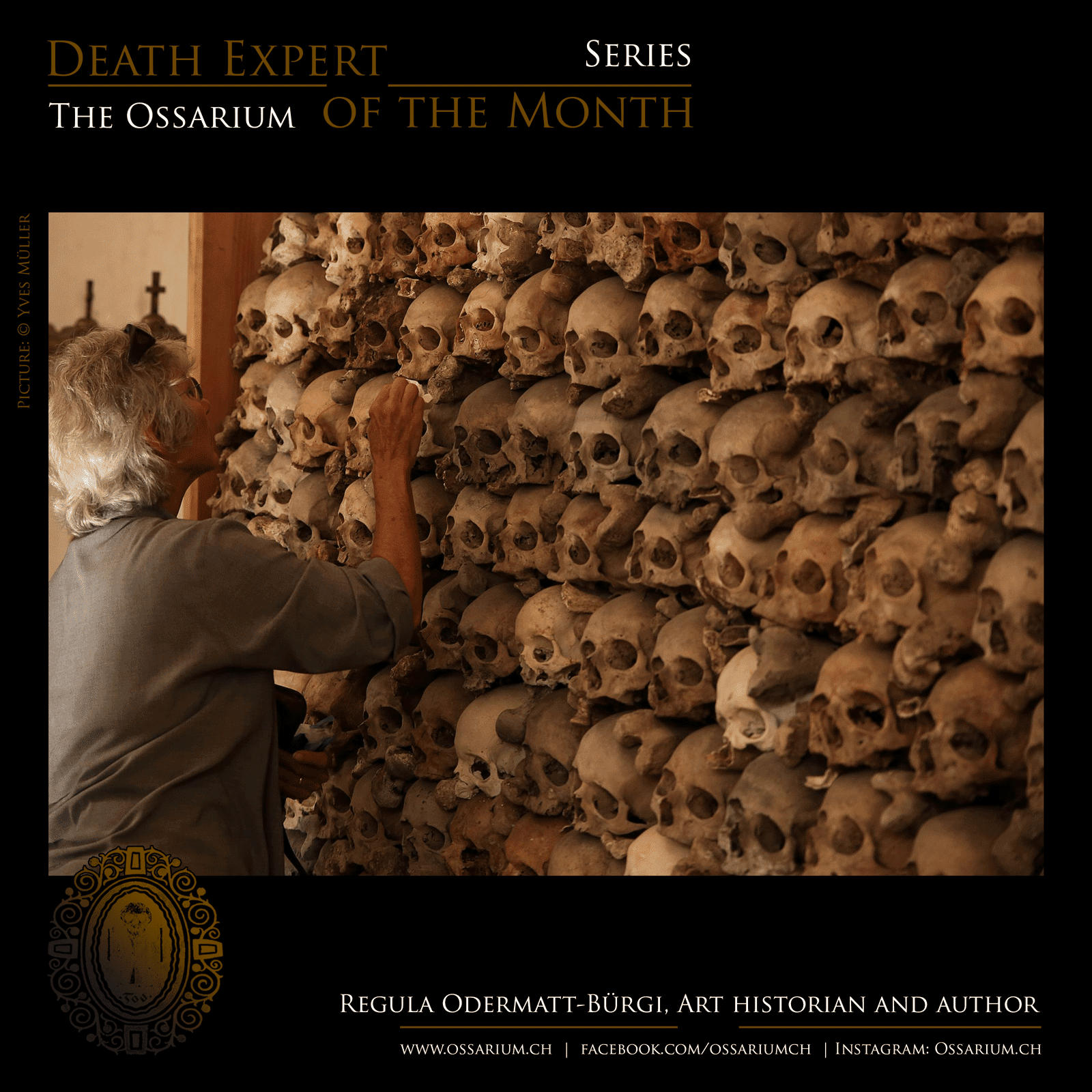

Regula Odermatt-Bürgi

Art historian and author, Stans

1 What does the picture show? How is it related to your occupation?

When my three and a half year old granddaughter looked at the Ossarium book, she wasn’t frightened or scared. There was only one thing that she was curious about, of which she asked me: “Where are the eyes? Where did they go?”

That conversation with her reminded me of a witch trial in central Switzerland. A woman called Lisibach was presumed to have asked Ludwig Widmer to light a candle in the ossuary and recite the sacrilegious words "Die lieben Seelen dürffend keins Liechts, sy gsehend nüt, denn sy keine augen habend”(“The brave souls shall not receive light, they see nothing, because they have no eyes”). Meaning that the effort of lighting a candle for the souls of the deceased is a waste, since – without eyes – they are unable to see it anyway. This blasphemous slogan was supposed to renounce the “Cult of the Dead” which believed in the possibility for the living to shorten or temper the time of the deceased in purgatory through offerings, prayers, donations, sacred masses and – like in this case – lighting a candle in the ossuary.

The deceased that cannot see, and also cannot hear is completely isolated from the plane of the living. He/She is out of reach, and therefore “dead” in every sense of the word. Lisibach probably wanted to disavow Christianity by renouncing the belief in resurrection and a life after death.

Many years back I was contributing a text exploring Austrian ossuary buildings (Karner) to an art history seminar with the topic “architecture with central structure”. Based on this I decided to write my Master’s thesis on the topic of ossuaries in central Switzerland. Apart from examining the architecture and iconography of said buildings the focus of my work also covered aspects concerning their usage of religion and folklore.

2 What does death represent for you personally?

My father was a country doctor. Therefore it was very natural to discuss topics such as disease, childbirth, and death at our dinner table. Death has been a part of my life since I can remember and it is a natural part of it. In no way is it a scandal, how Elias Canetti calls it. I hope that I will be able to accept death with dignity, even though I wouldn’t say that dying is a simple matter. After all, birth and death are the cornerstones of our existence.

It may be, at this point, that I am dealing with the topic too pragmatically. I can’t know for sure what I will be thinking and feeling, if I will be afraid, if I will revolt against it or simply despair of it when the time comes. The thought of escaping into the concept of reincarnation is however alien to me. Why can’t we let go? Why doesn’t it suffice to pass on our heritage to the coming generations? Why do we want to force the experiences of previous lives on them, and therefore deny them their right to create something truly new by themselves?

I simply try to live my life as intensely as possible. It was good, nice and happy – but it is enough already, I don’t want to live another life.

3 Can you tell us about an event related to death that you will never forget?

When I was about four years old, a neighbor on our street died and was laid out in her house. Together with a friend we wanted to see her, so we snuck into the house of said person. It wasn’t the room lined with black cloth, nor the green plants in the big buckets, the candles, the smell, not even the waxy looking woman in the open coffin that sacred me. It was a monotonous chanting that made the biggest impression on me. There was a person we called “Fiifi-Beterin” (roughly: fiveish prayer woman), because she was repetitively reciting The Lord’s Prayer (“Vatter unser”) and the Hail Mary (“Gegriist seischt dui Maria”) honoring each of the five wounds of our Lord Jesus Christ. Since then, it has scared me every time I hear the singing voice of such a woman, while I pay my respects to a deceased person, even though I know that someone will be singing every time. This tradition died in the 1960s, and I was searching for a recording of it, together with the composer Mela Meierhans. We couldn’t find any recorded proof of this custom, either in Valais, in central Switzerland, or any other catholic places in Switzerland.

My view on death has been heavily influenced by the memory of my mother. She died when I was six and a half years old. Not long before her passing, she joined us at lunch in her blue robe and asked us with her usual liveliness: “Promise me that I won’t have to go to the chapel of the deceased after I die”. We were puzzled, as it was quiet common in these days to lay out the dead at home. The dead were only transferred into this cold, dismal chapel at the hospital if their home was too small (for example families with many children and small homes). We promised her, that she won’t end up in the chapel, but our curiosity led us to ask her for the reason about this inquiry. She simply answered that she does not want to be cold. Even when we insisted that a dead person can’t feel warmth and cold anymore she persisted with her opinion.

Every time I see the body of a deceased person laid out in a public space like a funeral chapel, I can’t shake the feeling that this person is freezing. This doesn’t happen when I see an Urn, as the body is absent in such a case. The feeling is particularly strong when the deceased is laid out in a former ossuary building or in a funerary chapel within the cooling catafalque. The reason is because this element disturbs the intention of those rooms and the harmony that is necessary to say farewell. I prefer laying out the deceased at home, as it feels more comforting to me. The deceased, right after death, feels more alive in such a situation. The spirit still seems to be present and one can talk to the beloved person and feel like he/she is listening. Over the course of time the body changes and the features convert to a more dead-like appearance, as if the deceased is slowly leaving the place. One can take the time to accept this, and letting go seems more natural to me.

April 2018

Marek Jeziński

Dept. of Journalism and Social Communication

Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń, Poland

1 What does the picture show? How is it related to your occupation?

The picture shows the tomb of St. Lunarius (Les Gisants de Saint-Lunaire) in the small town of Saint-Lunaire (Bretagne, France). This austere Romanesque church was built in the 8th century and inside it I found one of the most beautiful treasures of early Christianity in this region; The grave of Lunarius, which dates back as far as the 6th century. The grave appears raw, harsh and primal. It is neglected, never gets any visitors and is somehow ignored. The place was filled with the rays of the afternoon sun, peaceful, calm and pure, what made it a real passageway between life and death. I had the possibility to look at this vault 15 centuries after Lunarius’ death and it calmed me down, and created a feeling of slient and genuine fascination. I felt that the church itself was a threshold between life and death. I think, in such a place you can experience the power of both death itself and human endeavors to make themselves socially remembered.

The latter seems to be quite significant for my work. I teach courses in sociology and anthropology at my university, so I use the figures of saints and the places of their cult as perfect examples for the formation and maintenance of a group identity, for the establishing of sacred places and for practicing the patterns of group integration. Moreover, from an anthropological point of view, the places related to death are crucial for rites of passage practiced in a given community.

2 What does death represent to you personally?

Nothingness. An empty space with no point of reference. I try not to think about death, but it happens somehow from time to time, sometimes quite frequently. When you have children, you want live on and on. Not to be an Immortal, but to watch them grow, and then to watch their children grow. After them the next generation and so on…

Death also means that you meet fewer people the older you are. People you used to know die, and you can experience the empty space left by them. Besides that, I’m a fan of popular music (especially of the rock genre), so I feel really sad when a musician I like dies. To name only a few who passed away during several last months: Lemmy, Fast Eddie Clark, Chris Cornell, Chester Bennington, Mark Smith, Tom Petty, Zbigniew Wodecki, John Wetton, Greg Lake, Allan Holdsworth, Malcolm Young, and first of all Chuck Berry and David Bowie. The pain is that this list will be inevitably extended.

3 Can you tell us about an event (preferably in the context of your occupation/work) related to death that you will never forget?

So far I actually had limited experiences with death in my close family or at work. The one I want to share with you is rather a personal than a professional one. When I was 16 my grandma Janina died (she was the mother of my mother). My grandma was with me from the beginning of my life, so I did not remember a world without her. She took care of me and our house in my early childhood. Some day she had a brain stroke and was half paralyzed for 9 years. So my family had to take care of her (which was uncomfortable, especially for her).

So when she died, it was a tough time for me as a teenager, as you may guess. I believe, I passed it through with the necessary sensitivity. It was a sad and depressive time and I had bad emotions. I still remember her reading to me from the children’s books, playing games with me and telling me fairy-tales about knights, gnomes, fairies, or princesses which had to be released by the brave men. Anthropologically speaking, in her talks I experienced for the first time a universal structure of myth…

March 2018

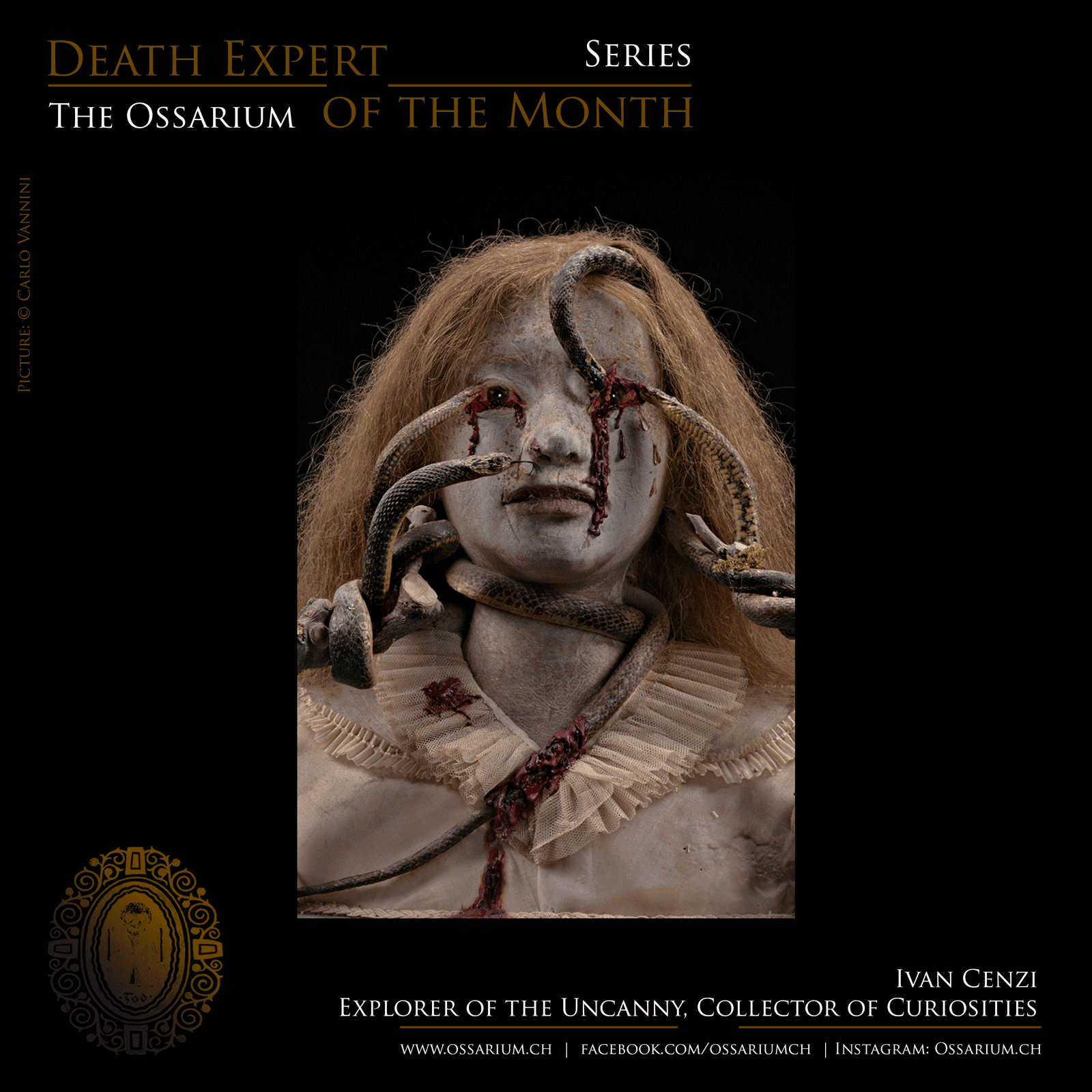

Ivan Cenzi

Explorer of the Uncanny, Collector of Curiosities, Rome

1 What does the picture show? How is it related to your occupation/work?

This is a picture taken from His Anatomical Majesty, the fourth book in my Bizzarro Bazar Collection.

It shows "The Punished Suicide", an artistic preparation by anatomist Lodovico Brunetti (1813-1899), currently on exhibit at the Morgagni Museum in Padua.

In 1863 this 18-years-old girl committed suicide, and Brunetti demanded her body be brought to him in order to experiment with tannization, his anatomical preservation technique. He made a cast of her upper torso, skinned her face (carefully preserving her hair), tannized it, and laid it out over the plaster cast. He then mounted some taxidermied snakes as if they were devouring the girl's face, to represent the eternal punishment she would have to endure in Hell for attempting suicide.

This might seem gruesome and completely crazy at first, but the story doesn't end there: Brunetti showed his "Punished Suicide" to the girl's parents, and they praised him for how perfectly he had protrayed their daughter; he even took this preparation to the 1867 World Exhibition in Paris, and won a Grand Prix for it.

And this is really striking: to us, this looks like the work of a mad scientist, but it was perfectly acceptable in its own time.

This is because our relationship with death has changed so much over just 150 years, and the taboo of death (removal/medicalization of the corpse) didn't arise until the early 20th C.

Besides being a wonderful intersection between art, anatomy and the sacred, "The Punished Suicide" is also a complex and wonderful reminder of how society’s boundaries and taboos may vary over a short period of time.

It is a perfect example of the work I'm interested in as a writer and as an "explorer of the uncanny": my way of proceeding is to exploit curious, often forgotten stories to lure people into a more in-depth discussion on sensitive topics. Whenever there's something that disturbs us, if we care to go beyond the initial shock we will always find deeper and deeper levels of insight and meaning. That's the beauty of liminal territories - they can teach us so much about the boundaries and fronteers of our own culture.

2 What does death represent for you personally?

Death to me is a reminder of our nature. "Mankind is kept alive by bestial acts", Brecht famously wrote: but mankind also ends with a bestial act, death.

Yet we do not like to see ourselves as animals, and all of our culture is an elaborate construction to set us apart from the so-called natural world (when in fact, how can anything be outside of nature?).

Our Western culture has built geometrical abodes and walled cities, we have tried to ban violence and "primitive" behaviour from our societies, we denied our bodily fluids, embalmed our dead so they don't dissolve or buried them in mausoleums so they don't return to earth, we elaborated intricate symbologies and beliefs - all in the attempt of proving that we are "more" than mortal primates. In the attempt of escaping the concept of havel havalim, "vanity of vanities", that haunts us from time immemorial: if death is to erase all traces of our passage, everything seems futile.

This fear of impermanence is what makes any human endeavour so beautiful, and so quixotic at the same time.

In my experience, embracing death as a part of the natural movement means that life can become much more like a dance, or a dream. When you think about any mystical or spiritual message (from Christ to Buddha, from Sufism to Lao Tzu, from the Vedas to Bodhidharma), they all boil down to the same core advice: don't believe too much in this reality! Even modern physics seems to suggest something along those lines. If you succeed in unlocking this perspective, you might find that achieving stuff, or "becoming" someone, doesn't matter all that much. In the end, domesticating death means learning to be lighter on your feet, while you're dancing your life away.

I think death ultimately reminds us we are part of a cosmos we cannot fully comprehend. How much wonder and excitement and enchantment and sadness and terror and beauty, in this!

3 Can you tell us about an event related to death that you will never forget.

Some years ago, as I was driving home one night on a badly lit road, I saw something on the runway and managed to avoid it at the last second. It turned out to be the body of a woman who had been run over.

I diverted the incoming traffic by placing my car in front of her, flashing lights on; I called an ambulance and immediately got down to see if I could give her first aid, but the woman was already dead. She evidently had been lying there, face down on the pavement, for some time: no sign of the hit-and-run driver. Other vehicles stopped by, and a little crowd of people gathered around the body. It wasn't a nice sight: the body was badly broken, and one leg had been severed. But what really impressed me is that there were some people, among the crowd, who were so in shock that they just couldn't believe the woman was dead. "That thing cannot be her leg", they kept repeating. "She must be alive", they said, still they wouldn't dare to touch the body.

I had never witnessed firsthand such a strong, almost child-like denial of reality.

When we read about the removal of death from every-day experience in academic papers, it's an abstract thought. But there it was in action, the most classic psychological denial: we stood confronted with a violent, ugly, all-too-common kind of death, and some of us just couldn't cope. Keeping death at a distance has left us with few tools to understand it, and in this case the very image seemed to be unbearable for some of the onlookers, their minds desperately tried to escape the thought of it. I felt so bad for them, and when I finally got home I stayed up all night thinking about what I'd seen. I felt sorry for the dead woman, of course; but I also wished I could help those frightened people to overcome their fears.

I believe some of the work I've done, namely my death-related writing, might be somehow related to what happened that night.

Contact/Website:

www.bizzarrobazar.com

www.facebook.com/bizzarrobazar

www.instagram.com/bizzarrobazar

Ordering of “His Anatomical Majesty”:

https://www.libri.it/museo-morgagni?tracking=53da49b67eead&id=14

February 2018

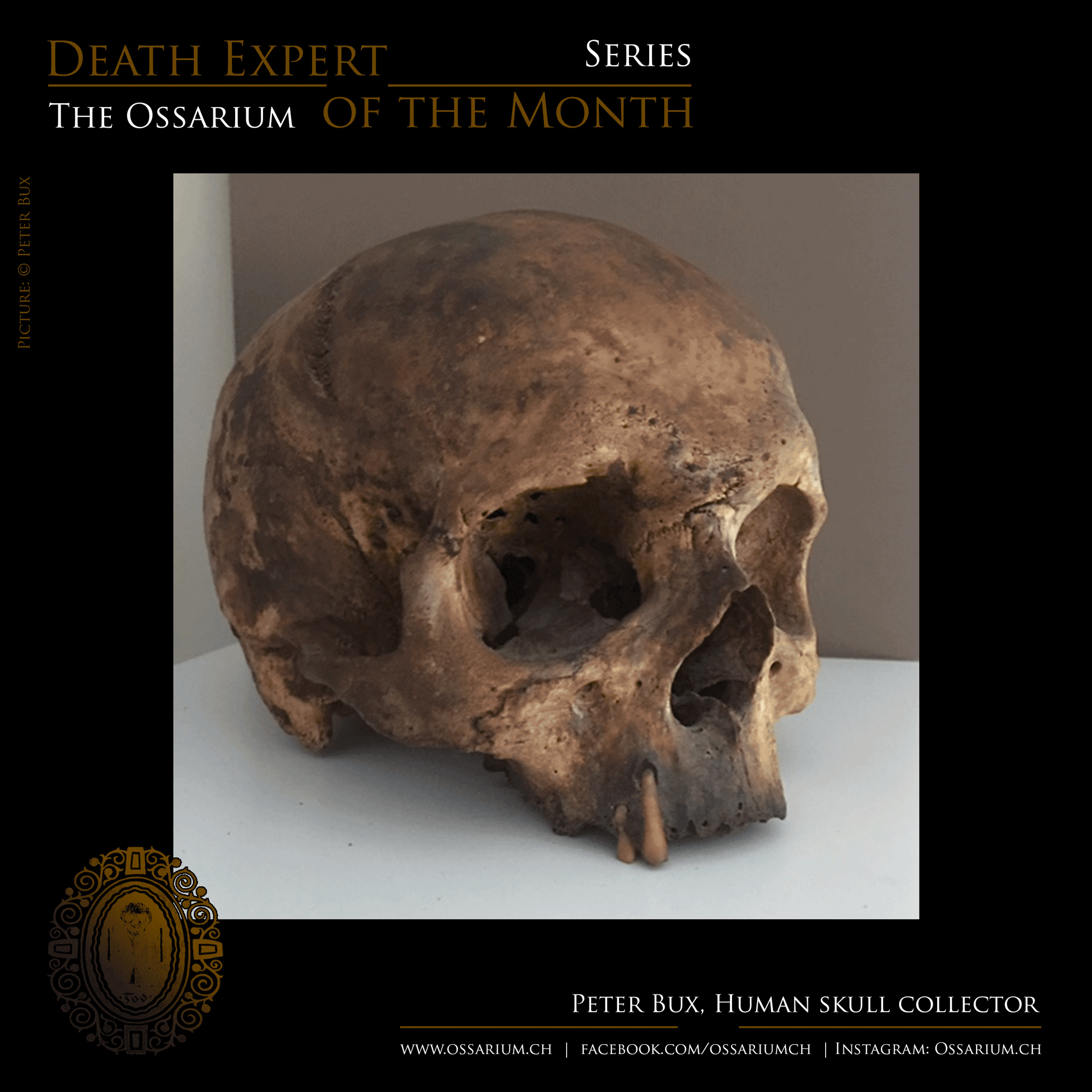

Peter Bux

Human skull collector, Deurne

1 What does the picture show? How is it related to your occupation?

One of my favorite skulls because of its rich patina. Some collectors specialize in medical, white human skulls, and that’s a great collection in its own right. I however have a love for the more “natural” look. The influence of nature and decay on the bone, gives it a rich color pallet making every single skull unique.

It does not, and to be honest, only a few people related to work know about it. Most people do not understand why one would like to collect such “gruesome” pieces of human anatomy. I wonder why they can appreciate beautiful stag antlers in a trendy decorated house and not the same part of anatomy when it comes to humans. The human race puts its own kind on a pedestal, forgetting that we ourselves are animals as well. And I do mean that in a biological way. A human skull is just a bony reminder of the most destructive and overpopulated animal on earth…

The way we treat human remains in western civilization is a direct consequence of religion and education. This is in contrast f.i. to the Papua, who keep their ancestors’ skulls in their homes, or the practice in the Toraja district of Indonesia where the mummified deceased are unearthed/disinterred and are dressed in new clothing every year, which is honoring them in the peoples’ own way. There are even big contrasts within Catholic religion, for example, compare All-Saints’ day in Europe and vibrant festivities like Dia de los Muertos in Mexico.

2 What does death represent to you personally?

Being an atheist, I believe it is the end of the journey. I am reminded about it every day, looking at my “Memento Mori” but do not fear it. The only thing I fear is leaving others grieving my departure. Death will bring nothing else but decay… To quote the painter Edvard Munch : “From my rotting body flowers will grow and I am in them, and that is eternity”

3 Can you tell us about an event related to death that you will never forget?

An aunt died a few years ago, and was cremated. As her ashes were scattered, birds flew in to pick the remnants. A family member looked at me in a horrified manner. To me personally, there was nothing awkward about it. It was feeding nature again, just like the Munch quote.

Contact: peter.bux@pandora.be

January 2018

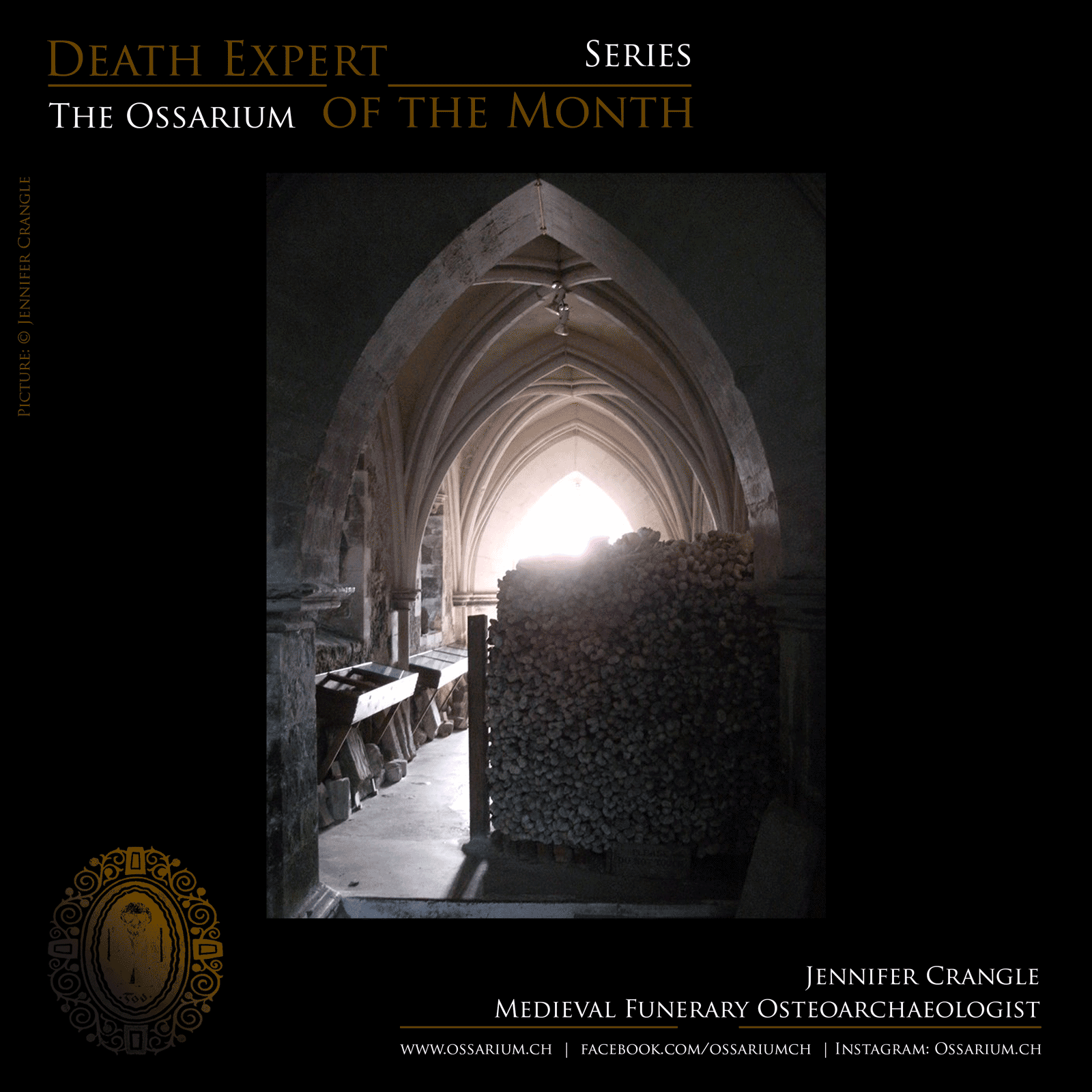

Jennifer Crangle

Medieval Funerary Osteoarchaeologist, Sheffield

1 What does the picture show? How is it related to your occupation?

The picture is of Hythe Ossuary (charnel chapel), in the Church of St Leonard, Hythe, Kent, England. I took this photo on my first visit there in 2009. It was a freezing, still day in February, and I was immediately fascinated. I was studying for my MSc in Osteoarchaeology at the time, and had links to Hythe ossuary via my Department. There was no real interest in the site apart from as an unusual collection of osteology to study or use in teaching. I, however, could not stop thinking of questions regarding medieval charnel chapels use, archaeology, history, culture. I quickly discovered that they were barely recognised in England and were very much misunderstood. From that point, they became my specialist research interest. After my MSc, during which I wrote my dissertation on English charnel chapels and Hythe, I completed my PhD. For this I focussed on charnel chapels, plus everything medieval people did physically to their dead, after burial. I am now a medieval funerary osteoarchaeologist, specialising in medieval charnel chapels. I am currently an honorary research fellow at the University of Sheffield, where I initiated the Rothwell Charnel Chapel Project, based on my research, in 2013.

2 What does death represent for you personally?

Honestly, I’m not sure. For medieval people, death used to be regarded as a continuation of life, in a manner of speaking. I see strong similarities between modern Catholicism (I was brought up as a Catholic) and medieval beliefs regarding death. Although I have been atheist since my early teens, I love identifying the links between past and present, regarding death, afterlife, and commemoration, even though I don’t believe them myself. I am intrigued by how people rationalise and explain death, applying their form of logic and compassion to make sense of something they have no control over. All cultures, communities, past and present, have their own way of coping with and understanding death, and the societal cohesion that results is of huge interest to me. The respect and love shown for the physical dead, disinterred from their graves and curated in charnel chapels, for me, exemplifies this.

Today, most people fear death, and regard people who study death-related issues as morbid. I think it is natural to be interested in death, and those who find it odd to research, are the unusual ones. But this is to study other peoples’ views on death. For myself, I don’t think I could say what death represents to me. I guess I will find out on my deathbed.

3 Can you tell us about an event (preferably in the context of your occupation/work) related to death that you will never forget?

Coming on a research trip in 2015 to Switzerland, to collaborate with Anna and Yves was pretty outstanding. We/I visited seven medieval and post-medieval charnel chapel sites while I was there. It was a defining moment for me, as it confirmed what I had discovered about English medieval charnel chapel sites, and made sense of many other aspects and features that I had noted in relation to English sites, but couldn’t quite decipher. Stans and Naters stand out particularly. We arrived at Naters mid-morning, to meet the chaplain who would let us inside. There were still votive candles burning at the window into the lower charnel chamber, beside the kneeler for saying prayers, and the prayer box for requests for prayers for the dead. These were lit by members of the community, who visited the charnel chamber as much as they would go to church. The use of imagery at Stans was striking, and it was clear that the design of the structures was deliberate, to almost force the visitor to experience the site in a particular way – visually (medieval memento mori and imagery of Ars Moriendi), mentally (recognising significant holy numbers, for example five steps into the charnel chamber) and physically (moving around the building in a specific procession). The ritual and liturgical use of the sites were revealed as we were shown around, and the intense symbolism inherent became apparent; for example the repetition of the numbers 3, 5 and 7; the use of light and dark; the links to prayer; the ‘sentient’ bones benefitting by being within a sacred building. It made me realise how significant these sites would have been to medieval people and religion, how they still were important to existing communities, how much more there is to research, and how misunderstood English charnel chapels are. I hope my research will continue to elucidate these beautiful places of commemoration.

Website:

http://www.rothwellcharnelchapel.group.shef.ac.uk/

https://www.facebook.com/groups/rothwellcharnel/

As a small "new year special" we decided to upload part four of the Death Expert Series a little earlier than usual:

Yves Müller

Photographer, Zurich

1. What does the picture show? How is it related to your occupation?

In the picture you can see me taking a photograph of the small ossuary in Dietmannsried (Germany). I believe it clearly represents what Anna and I are doing; we are searching for ossuaries that have been forgotten or just left to decay over time. This particular ossuary was a lucky discovery as we were in a different village, where one of the locals pointed us in the right direction. We would have walked right by it if we wouldn’t have known its exact location. So our work is influenced by local traditions and knowledge, tedious research, and long travel hours. In many cases – like our visit in Dietmannsried – the result is of interest to only a handful of people.

2. What does death represent for you personally?

Death is everything to me. There is nothing more powerful and more important in life than death itself. I am influenced by so much art and inspiration revolving around death that I could fill many lifetimes researching the subject. Apart from the visual forms and representations of death – which as a photographer are of particular interest – I believe death is a new beginning for us. I am not afraid to die, because I know that there is nothing we can do about it.

3. Can you tell us about an event (preferably in the context of your occupation/work) related to death that you will never forget.

Since my work revolves around this topic I could mention several occasions that I will never forget, but I believe more interesting to me, is not my perception of it, but rather the reactions we encounter during our work. I find it fascinating how people react when they enter an ossuary, or when I unpack my equipment to take some pictures of a person’s remains. There seems to be an invisible barrier between them and death, over which I am “trespassing” while taking my pictures. Most of the time people try to hide this, but I can sense their discomfort in such situations. It is almost as if they have the subconscious need to protect “their” dead against an outsider. This particular feeling only lasts a very short time. After a couple of seconds it usually dissipates, once they see that I treat my motifs with the utmost respect they deserve.

Website: www.ossarium.ch

December 2017

Guy Labo-O-Kult

Painter and Tattoo Artist, Biel/Bienne

1 What does the picture show? How is it related to your occupation/work?

In the picture, I am painting (the painting is entitled "Kairos"; Kairos is an immaterial concept of time that is not measured by the clock but by feeling, i.e. when you know it is the right time to act).

Painting, together with drawing and tattooing, are my favorite artistic activities.

My artistic work is primarily about one guiding theme, skulls. I start my days by drinking my coffee and sketching a skull. A skull is not only aesthetically fascinating, it is also a powerful symbol for many different cultures.

2 What does death represent for you personally?

Death for me is introspective. My interest in death is a search for depth in a superficial world of distraction. It is an inevitable statement in an artificial society. It represents the culmination, the final act of life, an elapsed time, a measure of our possibilities. In life, as in death, nothing is given, nothing is lasting. The idea of death offers a hope of tranquility which helps me to focus, and the use of the image of death in my everyday work settles me.

3 Can you tell us about an event (preferably in the context of your occupation/work) related to death that you will never forget?

When I held my first skull in my hands and I could examine it from every angle, or the very first time I found myself surrounded by thousands of human skulls in the catacombs of Paris, I felt a deep and comforting peace. But I also felt like a kid in a candy store...

Website: www.labo-o-kult.com

Picture: Ka L-O-K

November 2017

Dr. Janine Kopp

Historian and Journalist, Lucerne

1 What does the picture show? How is it related to your occupation/work?

The picture shows brown chunks which look similar to rocks, and give off an aromatic smell. I discovered them during the research for my dissertation called “Menschenfleisch” (Human flesh). They were stored in a supposedly empty wooden pharmacist box from the late 18th century and belong to the pharmaceutical collection of the Basel Historical Museum. The label, “Mumia vera” implied that they are remains of an Egyptian mummy, which were shipped to Europe for medicinal purposes. A newly conducted analysis however shows that this isn’t true, making the content counterfeit. In fact the box actually contains human remains from modern times. The analysis further revealed that the “mummy” consists of a coccyx (tail bone) and other material that was liquefied in a human skull, thus verifying that, although not ancient, the brown chunks are human remains after all.

This picture was important for my research, as it confirmed the main thesis of my work; that the content of such pharmaceutical ointments and potions, which were legally sold in pharmacies, didn’t consist of genuine Egyptian mummies, but rather of body parts like fat or flesh of executed criminals.

2 What does death represent for you personally?

Due to my work, I concern myself with human remains used as medicinal materials rather than focusing on death itself. In ancient times death was a part of everyday life, while nowadays we try to push it as far away from our lives as possible. Death scares contemporary people – I too know this fear.

3 Can you tell us about an event related to death that you will never forget.

I mostly remember reactions of people who were bothered by how disgusting these practices were in the past or how macabre people supposedly were in those days. One tends to forget that human remains still make up a big part of modern medicinal science. In fact, human body parts are used to a large extent in plastic surgery, such as using body fat for collagen plumping in lip augmentation. Another example, are recipes on the internet for pizza containing placenta to give women strength post childbirth. Thus, I ask myself if older customs were really that macabre after all.

Website: www.janinekopp.ch

Picture: Janine Kopp

October 2017

Oskar Ters

Historian and Teacher, Vienna

1 What does the picture show? How is it related to your occupation/work?

In this picture I’m entering and exploring a recently opened crypt, which has been sealed for more than 300 years. We opened it to ascertain, if the dead, who were catalogued in the books of the monastery, were really buried there and how the coffins were made.

2 What does death represent for you personally?

Death is the only thing in life that cannot be dodged. I fear him the most, although I’m confronted with him daily.

3 Can you tell us about an event related to death that you will never forget.

In a locked coffin we opened, because there was a risk it could break, we found once a mummified body. That’s not unusual, for we have a lot of mummies in the crypt. However, I was flabbergasted, when we discovered under the right hand of the mummy a small wooden whistle. It was there so that in the emergency of being buried alive, the concerned person could have called for help. Astonishing, because the body was more than 300 years old, so apparently the fear of being buried alive also existed in the baroque era.

Picture: Oskar Ters